Playing Jokes: Video Game Jingoism and the Falklands War

A story of two British computer games, leaky group paradigms, and the boundaries of bad taste

Deep in the Southern Ocean, northeast of the Antarctic Peninsula, sits a craggy spit of mountainous land shaped like a pachyderm’s head. Elephant Island is uninhabited, but never mind that. Imagine you’re standing at its frozen center, snow piling up around your ankles. You scoop this snow into your hands, packing it tight, giving it good air-cutting curves. You’re an ace pitcher, incidentally; you’ve got a superhuman arm. You wind a throw and release your grip, launching a snowball high into the air. It recedes from view, disappearing in the glare of sunlight, before crashing to earth 660 miles away on an archipelago smaller than the state of Connecticut, the Falkland Islands.

Today, the islands are most often remembered for the conflict that rocked them during the summer of 1982. In April of that year, a naval task force steamed some 8,000 miles from England to recapture the Falklands from Argentina, which claimed and still claim sovereignty to the Islas Malvinas, as they are known to people of that country. War was never officially declared, but the fighting was real enough. 905 people died that the Union Jack might again fly over Port Stanley. The struggle was a “moral and strategic step in the recovery of Britain and the West from the deadly malaise into which they had fallen.” The struggle was “a fight between two bald men over a comb.”

What played as farce to some was for others a matter of national pride and principle. Certainly most of the British people stood squarely behind their government. Public approval of Downing Street’s response rose from 68 percent at the start of the war to 84 percent by its end in June.¹ This fervor found patriotic expression in contemporary culture; comparisons to the Second World War were rife. Victory in the Falklands was said to reverse decades of diminishing global relevance and self-doubt, the smallness of the stakes notwithstanding. For some, the war was nothing less than national therapy, Britannia speaking affirmations in the mirror of her shield. “All of a sudden, thoughts and emotions which for years have been scouted or ridiculed are alive and unashamed,” wrote Enoch Powell, a conservative member of parliament, who himself served in World War II. This mood, “a quiet, matter-of-fact unanimity of purpose has painted out, in a way irresistibly reminiscent of 1939 and 1940, differences of class, education, prejudice and party. The British are never so formidable as when they are in this mood.”²

A mood not to be confused with jingoism, Powell insisted. In his view, the nation’s demeanor was one of dignified resolve, never mind a few “exceptions and divergent strains.” But such dignity was not to be found everywhere. Consider the case of Osvaldo Ardiles, an Argentinian footballer, who was jeered during the semifinal of the FA Cup, one day after fighting in the Falklands had commenced. Ardiles, who played for Tottenham Hotspur, was harangued by fans of Leicester City F.C., who chanted “England, England, England” every time he touched the ball (Tottenham fans reportedly placed club over country, singing “Argentina, Argentina, Argentina” in return). This episode was commemorated in a song, “Buenos Aires,” by the Macc Lads, a punk band from Macclesfield, England.

There was a load of bloody fairies in Buenos bloody Aires;

With greasy hair and sweaty bums, they’d never heard of Boddington’s.

It were a different culture and a different race; no chippies in the bloody place.

You can keep that poof Ardiles ’cause we’re going to have your Malvinas.

Toe-curling stuff. A burp of unbridled chauvinism, if you believe its sincerity.³ Fitting, too, inasmuch as it keeps with the tradition of “Macdermott’s War Song”, the music-hall ditty that gave rise to the word jingoism itself. Regardless, “Buenos Aires” proves that not all of Powell’s countrymen comported themselves as he did. So the Lads aren’t bigots; what of the people they’re sending up?

A hundred years after “Macdermott,” humankind had forged new frontiers for expressive bellicosity. By 1982, the home computer revolution was well underway, and computer war games, though still in their infancy, already had a five-year history behind them. Nationalists, once restricted to music and movable type, could now rattle their sabers in the medium of bits and bytes, and hobbyists could wage virtual war alongside them. In 1977, Walter Bright converted a board game he’d designed, Empire, into a turn-based strategy game for the hulking PDP-11, a minicomputer by the standards of the day but one as tall as a man once disk and tape drives were added. Two years later, Strategic Simulations published the first commercial war game, Computer Bismarck, a recreation of the eponymous ship’s last battle in 1941.

But the Falklands War was the first occasion that software developers could simulate actually existing war even as events unfolded. In fact, the first game about the crisis, Obliterate, would debut four days before Britain’s task force arrived at the islands.⁴ It was soon followed by another Falklands-inspired game, Jeff Minter’s Bomb Buenos Aires. As that inflammatory title suggests, both games would ignite controversies that burned like roman candles, brightly, and to the relief of their creators, briefly. These controversies stemmed from the games’ dialogic quality; they were developed and deployed with a speed that enabled correspondence with current events.

But speed is only part of their story. They are remarkable, too, for their very nature. In content and structure they operate like and are redolent of jokes. Call them joke-like games. Like jokes, the element of surprise is key to their appeal. What little gameplay they possess is narrow and constrained, developed just enough to shuttle players to a cheeky denouement, an electronic punch line. And like jokes, they proved highly perishable, not least because the crisis in the Falklands ended in a matter of weeks, Argentina having surrendered on June 14, 1982. Reporters soon moved to juicier stories, including the birth of William, Prince of Wales, a week later. The first Falklands games, having embarrassed their creators, having been expurgated or retracted, were all but forgotten.

But the games aren’t dead, merely dormant. Like even the hoariest jokes, they shiver into being, rejuvenated, when someone learns of them, plays them, tells about them. Because joke-tellers aren’t like the archetypal wise man in a mountaintop redoubt, or the sage who shares his knowledge, but only reluctantly, after being sought out and persuaded of the hearer’s fitness. No, the teller of jokes is incontinent; he cannot help himself. He cannot resist impressing you into the informal brotherhood of joke-knowers. He finds you in an unguarded moment, taps your shoulder, beckons you close, and asks: Have you heard the one about…?

So, have you heard the one about the journalist, the programmer, and the undeclared war over two British dependencies? It goes something like this.

I. Hydraulic Shock

Gary Zabel was defiant. “I don’t feel guilty about the game at all,” he told a reporter. The game in question? Obliterate, a modest submarine simulation that had lived for nearly a year on Britain’s Prestel service without sparking controversy. But that was before Zabel and his colleagues changed the game’s scenario, making it “more up to date and topical.” Topicality generated fresh interest, but not everyone liked what they saw.

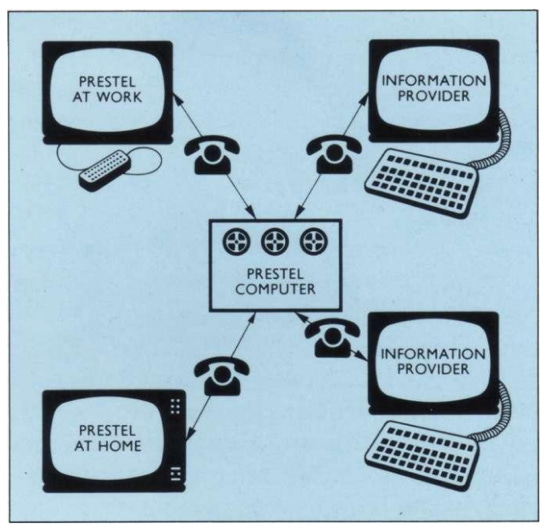

Zabel was then editor at the Bolton Evening News, the flagship of the St. Regis Newspapers group. For months he’d been working on an ambitious project handed down from headquarters: to establish a newspaper presence on Prestel, an interactive news and information service created by the United Kingdom’s General Post Office in 1979. Prestel communicated with its users, and they with it, by means of viewdata, a communications protocol that encoded information by modem and sent it over telephone lines from one of several GEC 4000 minicomputers.

Subscribers called these computers from the comfort of their homes, many from ordinary television sets that had been equipped with keyboards and special adapters. By the end of 1980, Prestel was operating 18 retrieval computers with 1500 ports of combined access.⁵ Though markedly different from the internet, chiefly in its centralization, Prestel and other viewdata services, such as France’s Minitel, anticipated the internet by almost a decade.

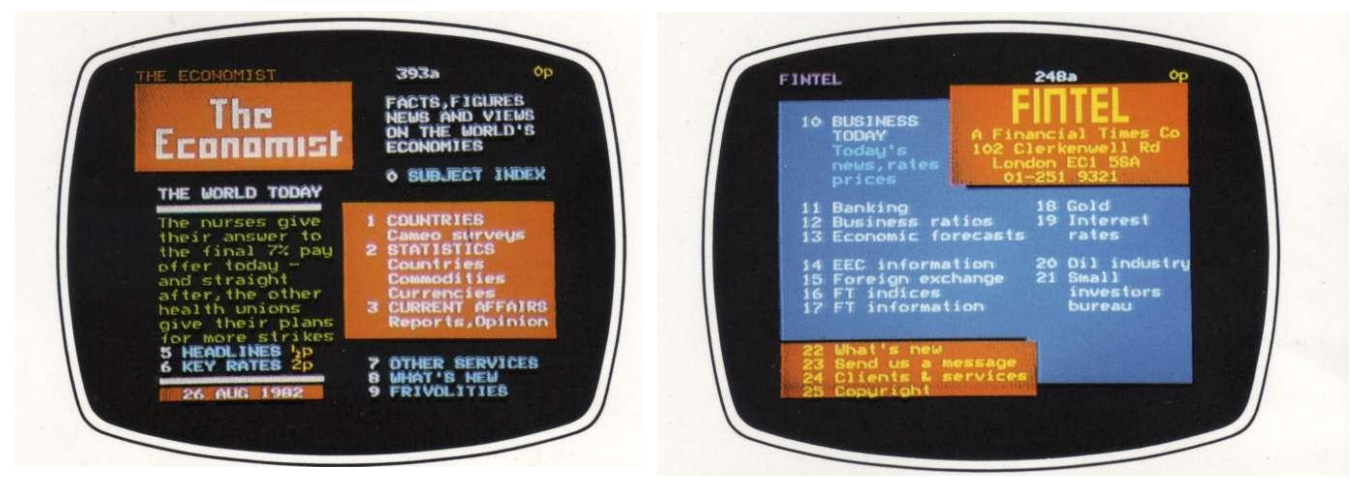

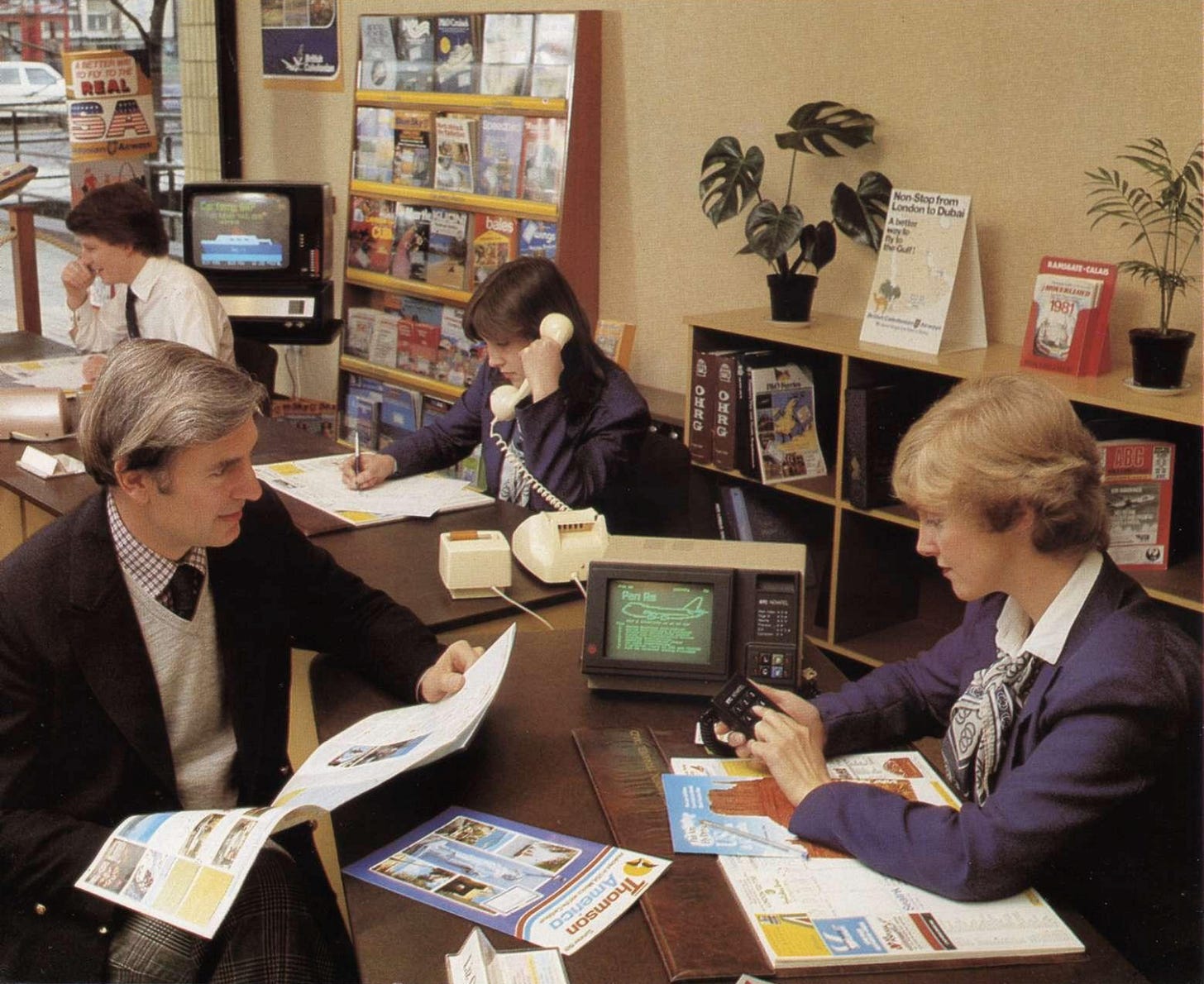

In October 1981, British Telecom was separated from the Post Office and turned into a state-owned telecommunications company, and Prestel went along with it. To juice Prestel’s value proposition, and thereby justify its expensive hardware, BT enlisted information providers to create enticing content for the new service, some of them household names. The Economist had an outpost on Prestel; so did the Financial Times, operating as Fintel.

These providers published news hubs called pages. Each page comprised several subpages, frames on which text and crude graphics were rendered. Each page was assigned a unique address, one to nine digits in length, and Prestel users navigated the service by entering these addresses on keypads. Related pages were grouped under topical headings, and full-color directories were mailed to subscribers on a bimonthly basis. Prestel also maintained a subject index on the service itself, located at page 199. If this sounds a bit like the World Wide Web during its directory era that’s no accident. Prestel aimed to be the Web of its day, rendering paper media obsolete, or at least making them seem stodgy and old-fashioned by comparison. But paper proved to be a redoubtable technology as it has many times since, and one not easily replaced.

At its peak, Prestel had just 90,000 active users, a small fraction of BT’s telephony customers. Prestel hardware was pricey, which throttled the rate of adoption, and its customers didn’t enjoy the subsidies that helped make Minitel a success in France. Startup costs weren’t the only barrier to access; the service itself was expensive to use. Customers paid a £12 quarterly subscription fee plus the cost of their telephone calls, and some information providers charged additional fees for access. Certain pages of The Economist, for example, cost a penny per view. But such was the price of being first to market. Surely prices would fall as Prestel’s subscriber count inched upward.

Early adopters such as St. Regis may well have consoled themselves with such reasoning. In any case, Prestel was too rich with possibility to ignore. It presented a potent if putative solution to a clutch of concerns: skyrocketing newsprint costs for one, customer retention for another, not to mention the fear of being outfoxed by tech-savvy competitors.⁶ Nor was the company alone in searching out new markets. The Birmingham Post and Mail, the Eastern Counties Newspapers, and the Yorkshire Post Newspapers had all leased Prestel pages “as an insurance policy.” Even the National Union of Journalists had leased twenty pages on the service. Gary Zabel’s paper, the Bolton Evening News, was among these pioneers, staking a claim on the information frontier, and betting that its focus on regional news would find paying customers on Prestel as it had on the newsstands of Greater Manchester.

In February 1980, St. Regis unveiled its Prestel channel, Mercury 332. Named for the Roman messenger of the gods, a nod to the speed of the service, Hypnos proved more apt a handle, at least where growth was concerned. Prestel’s uptake was indeed hindered by high prices, but also by manufacturing shortages and marketing that courted self-sabotage. One commercial opens on a comfortable sitting room in which a television set glows with activity. On it, a sickly green cartoon hand beckons. The camera dollies forward while a shrill sustained note, seemingly lifted from a slasher movie, drones in the background. The camera moves in closer, the hand crowds our field of vision. We’re rooted to the spot, terrified, when the hand disappears, replaced by words in a chunky green typeface: “Hello, my name is Prestel.” “Please don’t be afraid,” it continues, “I’m perfectly friendly.” Which is just what a rogue computer would say before disconnecting your life support system.

Educating consumers, overcoming their reluctance: these were problems, to be sure, but they were problems for BT executives to solve. Of greater concern to Zabel and Wadsworth was the region in which sales were being made. Prestel’s emerging subscriber base was strongly concentrated in the southeast, in and around London, and this posed a problem for an electronic newspaper pitched at Greater Mancunians. St. Regis intended to recreate in cyberspace what it offered readers in print, but London’s Prestel viewers had little need of Mercury’s local focus. Zabel had always planned to include some national content; now he steered hard in that direction, effectively flipping Mercury’s content priorities. The Prestel channel would not supplant but rather supplement St. Regis’s core products, good old paper and ink. Mercury 332 became less a local newspaper than an entertainment magazine for general readers, “heavy on horoscopes, biorhythms, hypnotism, games, quizzes, competitions.”⁸ Its regional identity was reduced to “a fair sprinkling” of such information, namely that which appealed to tourists such as hotel and restaurant guides.

Games and amusements, meanwhile, had long been a staple of newspapers; why not electronic newspapers too? Games had universal appeal. In fact, a chess program was among Prestel’s earliest offerings.⁹

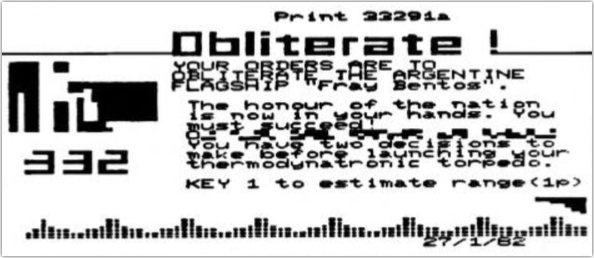

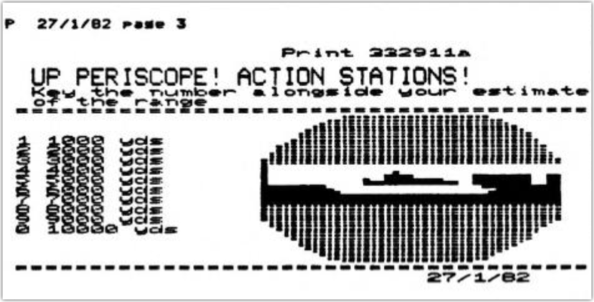

It was Bill Wadsworth, Mercury 332’s sales and marketing executive, who proposed the idea that eventually became Obliterate. He saw great promise for ad sales in Prestel’s interactivity and had been searching for a way to attract more reader attention. At last, he hit upon the idea of a game with a military theme: submarine warfare. Why submarines? “No idea,” Zabel said. “It just came up,” a product of “blue sky thinking.”¹⁰ Given the limited affordances of Prestel pages, it’s likely that form followed function. Obliterate could have only one of a few designs: the branching narratives of interactive fiction, for example, or a simple guessing game.¹¹ Obliterate adopted the latter option.

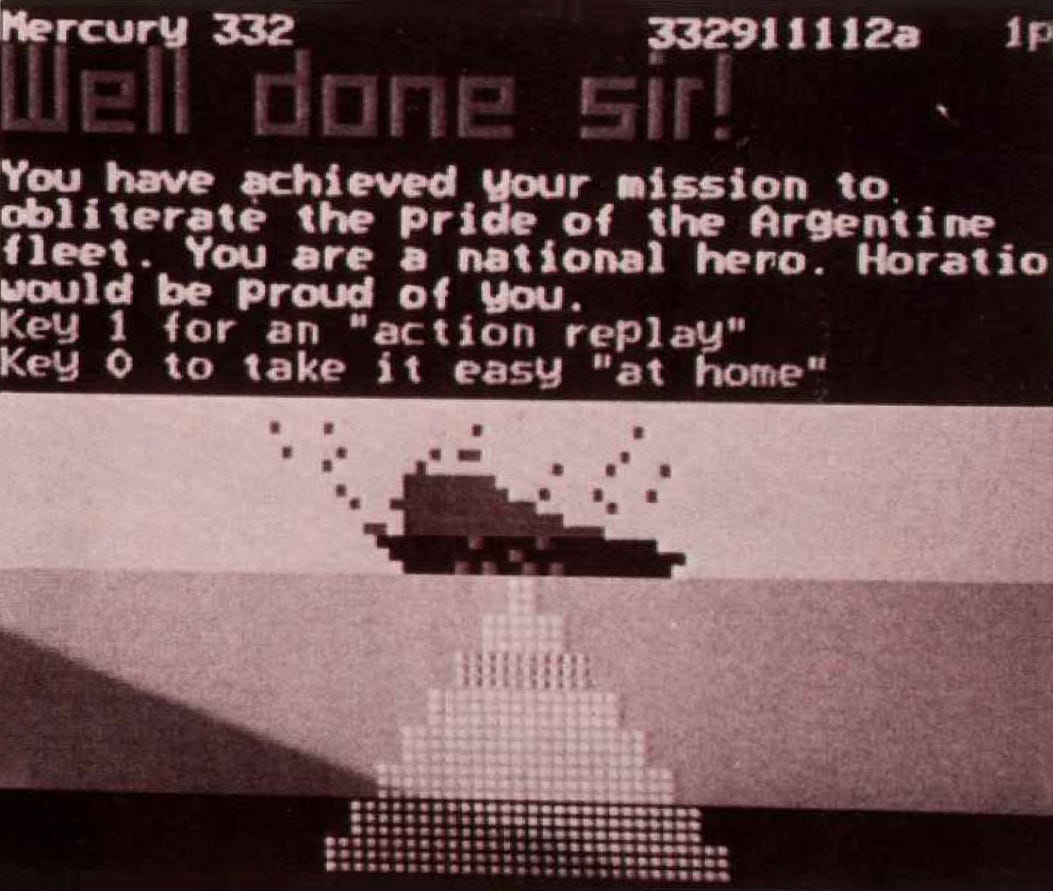

Its players assumed the role of a missile technician aboard the — what else? — H.M.S. Mercury 332. The game opened on a conflict in progress, one frozen in the stop-time of turn-based tactical games. In Obliterate’s scenario, players had the jump on an enemy battleship and the chance to sink it in one go, provided they could guesstimate two combat variables: the range separating the ships, measured in yards, and the time delay of the submarine’s “thermodynatronic” torpedoes. Zabel and Wadsworth made screen mockups on sheets of graph paper, including play instructions and flavor text, then gave them to a keyboard operator who translated their vision into the language of Prestel. “Row by row, Gary counted all the pixels out from the paper grid, and our office manager Carol and I counted them all in from the keyboard to the screen,” Wadsworth says. Each image was painstakingly stitched together, “pixel by pixel, line by line, to the screen as in a tapestry.”¹²

“It was all pixels,” Zabel recalls, “quite crude in today’s way of displaying images.”¹³ Indeed, the game’s graphics are chunky, rectangular, and abstract to the point of confusion. Squint and you can just make out the shape of a submarine, its conning tower and control fin. Few images of the game survive, and those that do are grayscale. But a Washington Post article reports that the game’s title was “printed over swelling blue-and-white waves,” giving us a sense of the game’s color. This article also reveals the extent to which players compensated for graphical crudity by giving free rein to their imaginations. The author, Tom Zito, writes in a breathless, gee-whiz register. Tongue-in-cheek, certainly, but evidence, too, of a player caught up in the game’s modest drama.

Finished at last, Obliterate debuted nearly a year before the Falklands War. In its first incarnation it referenced only historical naval glories. On loading the game, players were instructed to “Sink the Bismarck,” a reference to a 1960 war film, itself based on a World War II battle in which Royal Navy submarines sank the eponymous German battleship. If players were successful, Obliterate would display a screen hailing the victor as someone “Horatio would be proud of,” Horatio being, of course, Horatio Nelson, doomed hero of the Battle of Trafalgar. Patriotic stuff, but Zabel and Wadsworth’s intentions were whimsical, not nationalistic, as the game’s thermodynatronic torpedoes make clear. Search any military dictionary you like, you’ll never find an entry for this invented bit of technobabble. The game was born not from a passion for play but from problem solving. “Neither of us were that into video games,” Zabel says. “We were a couple of young guys enthusiastically trying to promote our service in a novel, entertaining way.”¹⁵ Obliterate, like other games before and since, was a means of demonstrating what computer hardware could do and be.

Having surfaced on Prestel page 33291a, Obliterate sat apparently inert, causing neither stir nor ripple. And small wonder: there were few players to attract in the first place. By one estimate, Prestel had just 15,000 subscribers by January 1982. British Telecom had even shut down some of its servers.¹⁴ The rosiest predictions for Prestel had wilted. Columnists were calling the service “a crashing disappointment” and “a technical triumph but domestic marketing flop.”¹⁶ ¹⁷ Undeterred, Zabel and Wadsworth continued Mercury’s transformation into an entertainment digest. Despite “a generally cynical belief that maybe half of what was being claimed for viewdata would be actually achievable,” Zabel still thought Mercury could be made into a new and attractive product, not a replacement for newspapers perhaps, but a supplement with dedicated readers and advertisers eager to reach them.¹⁸

And then on March 19, 1982, a group of Argentine metal workers brazenly raised their country’s flag over Leith Harbor on South Georgia Island, precipitating conflict. British attempts at diplomacy were rebuffed. Two weeks later, on April 1, Rex Hunt, governor of the Falklands, received a diplomatic cable now famous for its dry understatement: “We have apparently reliable evidence that an Argentine task force could be assembling off Stanley at dawn tomorrow. You will wish to make your dispositions accordingly.” Hunt mustered what defenses he could, even squeezing off a few rounds from his personal sidearm. But Stanley fell to Argentine marines just the same. What had seemed only swagger and effrontery from Leopoldo Galtieri, Argentina’s military dictator, was now a full-blown international crisis. But it would be twelve long days before the HMS Spartan, a nuclear-powered submarine, would arrive at the islands to enforce a maritime exclusion zone; a period of expectation and, yes, excitement, conditions that gave rise to a certain opportunism in the crew of another sub, the HMS Mercury 332.

By this time Obliterate had been on Prestel for close to a year. The game was a novelty within a novelty, a trifle on a Prestel service that few Britons had taken up. Obliterate was enjoyed by such visitors as Mercury had, but the game hadn’t appreciably widened the market for advertising sales as Wadsworth hoped it would. But then came the crisis in the South Atlantic and with it a pretext for refreshing Obliterate and restoring it to prominence on the channel. The plan, Zabel later told a reporter, was to “change the topic to become more up to date and topical”. This consisted in changing the game’s text to describe an Argentinian enemy rather than an anonymous one, and of playing an expressly British submarine commander. The game’s mechanics were left unchanged. Zabel and Wadsworth made just one other alteration, christening the enemy flagship Fray Bentos, a reference to a brand of tinned meat sold in the United Kingdom. “That was just a joke,” Zabel says. “We associated [Fray Bentos] with Argentina.” In fact, the company was originally located in the Uruguayan port city of that name.¹⁹

Thus revised, Obliterate was again pushed out to Mercury’s subscribers on or about April 3 where it enjoyed renewed attention. Readers keyed away at the game in greater numbers, now playing for Queen and country. A week later, brief notices about the game appeared on the front pages of the Telegraph and the Daily Mirror. So new were video games to the public imagination that both papers likened Obliterate to Space Invaders, never mind the lack of correspondence between the two. The difference was more than cosmetic, though, extending to the nature of each game’s narrative conflict. Blasting aliens was one thing; blasting human beings, even enemies of the state, was quite another. It didn’t matter that Obliterate was bloodless; a backlash was building, and quickly. In his Washington Post article about the game, Tom Zito quoted Harold Jackson, a reporter for the Guardian, who lamented the “terrible outbreak of jingoism in Britain.” When the Daily Mirror asked Sir Napier Crookenden, chairman of a British charity for armed forces, what he thought of Obliterate, he told the paper “it sounds in appalling taste.”²⁰

At last Mercury was getting the press it sought, but it was the wrong sort of attention altogether. Or was it? The company had struggled to connect with consumers; now the name of Prestel was on their lips. Even so, news of Obliterate had reached Bob Cryer, a member of parliament, who denounced the game as unethical and fretted that its players would come “to see war as nothing more than a game.” Years later, Zabel would dismiss this criticism as insincere, the hollow words of a “rent-a-quote MP” who had “jump[ed] on a bandwagon”.²¹ But in April 1982, the heat proved too much for Mercury, which subsequently withdrew the game, keeping the tempest teapot sized. In the first issue of a print newsletter mailed to Mercury subscribers, Wadsworth explained that despite being popular with Prestel users Obliterate was withdrawn because “we didn’t want to be accused of bad taste, especially as events were turning for the worse. We received several messages from users asking us to keep the game on. We hope to bring it back in one form or another as soon as we feel the situation is appropriate.”²² But that day never came. No sooner had it appeared in the public’s attention than Obliterate slipped from view, never to resurface.

That summer, Zabel traveled to New York City where he addressed the 2,000 attendees of Videotex ’82, an industry conference. In a speech later published as “Experiences of a Regional Newspaper Publisher on Prestel,” Zabel paints an ambiguous picture of Prestel’s future. His employer, St. Regis, was never as bullish as other early adopters, having set a risk ceiling of just 50,000 pounds per year. Two years into its venture, St. Regis wasn’t bleeding money, but neither was it turning a profit, nor drawing subscribers from its region. Most Mancuinans eschewed Prestel’s expensive equipment, not to mention the high cost of accessing the service. Zabel estimated that 40 minutes of prime-time Prestel cost users £2.84, or 71p after 6 PM when surge pricing ended. Compare those fees to the cost of a typical newspaper, between 14p and 25p. Prestel was no threat to the newspaper business so long as it maintained such high tolls. The boldest predictions for Prestel, that it would remake the business for local news and information, had not and would not come to pass. At the heart of the Obliterate episode was the irony that newspapers, not Prestel, brought Obliterate to the public’s attention. “Right now, we in the videotex industry still need newspapers more than they need us,” Zabel concluded.²³

Ultimately, it was the end of the Falklands War rather than any concession to good taste that doomed Obliterate to an early grave. The topicality that Zabel prized gave Obliterate a short shelf life. All too soon it was yesterday’s news, and St. Regis wasn’t in the archives business. Contacted for a statement months later, and facing down an existential threat from cable television, then set to debut in Britain, Zabel gave a feisty reply. “There’s a lot more happening in the world today to be critical of,” he observed. “There are so many things on the market from war films to war games to comics about war. I don’t feel guilty about [Obliterate] at all.”

He was right. Other developers were making war games, some of them about the Falklands War. An editorial in Popular Computing Weekly from May 27, 1982 bemoans the “great upsurge of programs with titles such as Falklands or Island Invasion.” The magazine vowed never to publish such “bloodthirsty” games––but it gave advertising space to one of them.

II. Grounded

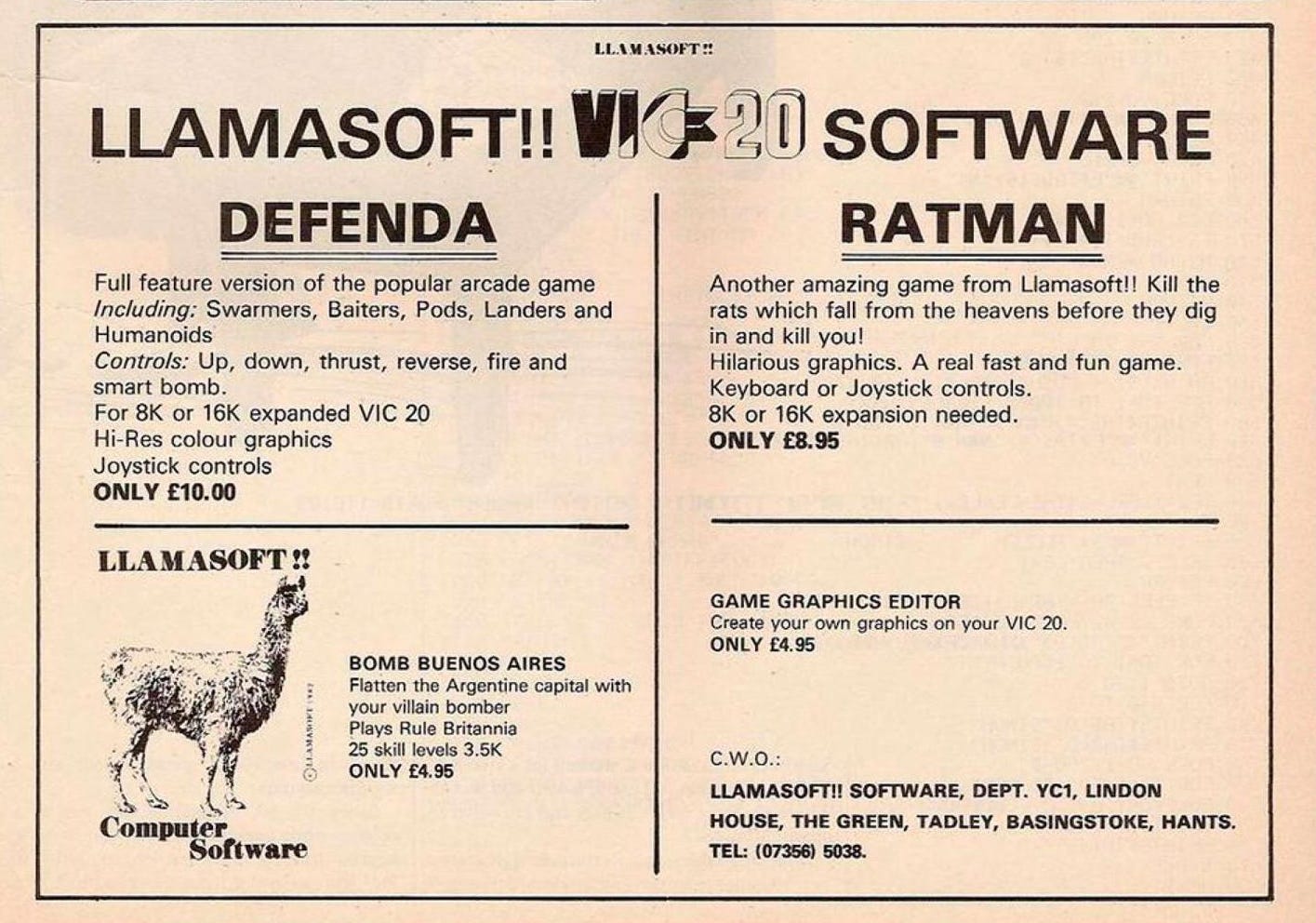

Meet Jeff Minter: programmer, rural Welshman, “scruffy hairy beast.” Minter is also a 40-year veteran of the video game industry. A gentle eccentric with a fondness for ungulates, Minter is known for score-chasing shoot-em-ups such as Tempest 2000 and Polybius, and for his sheer longevity. It would be easier when summarizing his career to name the hardware on which his games haven’t appeared. Known to his fans as Yak, a nom de high score, Minter attained early success with 1982’s Gridrunner, a turbo-charged take on Centipede; but his first games were made for personal computers such as the Sinclair ZX81 and the Commodore VIC-20. These games were rudimentary and derivative, scarcely bothering to conceal the source of their inspiration. Defenda hewed closely to Defender, Rox to Asteroids.

In 1982, Minter incorporated as Llamasoft and began issuing original games at a feverish pace, twelve in that year alone. This productivity was a testament to Minter’s talent and zeal, but also to the simplicity of his designs, which were sometimes borrowed from other games. That Minter could ship games so quickly made it possible for him to correspond with current events, tweaking them in the manner if not the medium of humor magazines like Mad. Hence the development of the game that by Minter’s own estimation was “probably one of the most shameful things in Llamasoft history, a joke which got out of hand.”

As the owner of a new software startup, Minter, just nineteen years old, needed products to sell. He rushed to create a library of games for his fellow enthusiasts, early adherents of a still-emerging hobby. Older titles such as Headbanger’s Heaven, a riff on Space Invaders, were dusted off for this purpose; but Defenda, Llamasoft’s breakout hit, was still months from release. And then came the Falklands War. Minter’s countrymen were riveted by the fighting, and in their absorption he sensed an opportunity.

He quickly wrote a new game, a clone of Air Attack, which itself was derived from Atari’s 1977 coin-op Canyon Bomber. Developed in 1979 by Peter Calver, a pioneer of British computer games, Air Attack was already considered as “old as the hills” when Minter put his own spin on it. In a neat inversion of Space Invaders, the game tasked players not with defending civilization but reducing it to rubble. The object of the game is simplicity itself: drop bombs on buildings, destroying them bit by bit, and more and more frantically with each pass. Players are limited to a single action, choosing when to press the key that controls the plane’s bomb bay doors. Timing is everything. Each stage ends when players land the aircraft atop a smoldering ruin where the city once stood, or else collide with an unleveled building.

By 1982, cloning Air Attack had already become a rite of passage for budding software developers, “one of those things that everybody did because it was dead easy to program in BASIC.” Minter’s take cleaved to the original game but for a curious detail; each building targeted for destruction sports an unmistakable Argentinian flag.

In the game first issued as Bomb Buenos Aires, Minter left Air Attack’s scenario and mechanics basically unchanged, altering only the graphics and sounds, and these to impart the zest of a crude comic patriotism. What had been an anonymous aircraft in Air Attack was now expressly a Vulcan, the bomber responsible for leaving a crater “sixty feet wide and half as deep” in the runway at Port Stanley airfield. At the start of each stage, Bomb’s players were feted by the soaring strains of “Rule, Britannia”, or as rousing a rendition as the VIC-20’s sound chip could muster. And then there were those Argentinian flags.

Indulging a yen for the imaginary destruction of real places — cities, landmarks, even the planet itself — has long been a pastime of certain fantasists, and often a profitable one. Just ask Roland Emmerich or the many directors of disaster films before him. Even Calver’s Air Attack was set in New York City, its players instructed to land there but only after “destroy[ing] all the buildings first by bombing them.” Perhaps it gave players a naughty frisson to imagine their bombs falling around the Chrysler building and the Empire State. But one wonders how many Air Attack players ever read those instructions, or whether they paid “New York” any mind. The structures in Calver’s game are stubbornly abstract, more bar graph than building; nothing about the game makes Calver’s choice of setting anything more than a artifact of automatic thought. New York was good enough for King Kong to smash; why not the aircraft in his one-button amusement?

Jeff Minter, acting impulsively in the manner of 19-year-olds everywhere, shared something of this blithe spirit. The “Argies” were in the news; what’s more, they were aggressors in a conflict that was even then unfolding. This was enough to justify a stab at relevance, adding the flavor, if not the substance, of politics into Minter’s clone. Plus, it gave him a readymade way to separate Bomb Buenos Aires from legions of other Air Attack clones. It made the game topical, to use Gary Zabel’s word.

Thus revamped, Minter sent copies of the game, recorded on cassette tapes, to the editors of computer magazines. He promoted the game in their classifieds section, enticing would-be players to “flatten the Argentine capital with your villain [read: Vulcan] bomber” for the low, low price of £4.95 (about £16 in 2023).

The backlash wasn’t long in coming. For Minter, the game was tongue-in-cheek, a message-free spoof of voguish and untutored nationalism. But when Bomb Buenos Aires was mentioned in the center-right Daily Telegraph, he got a stinging lesson in the unintended consequences of semiotics. In a news brief, the paper praised the “jolly” experience of “releasing thousands of tons of bombs on Buenos Aires,” a glib reception that horrified Minter. He had unwittingly buttressed the paper’s case for war, and inadvertently aligned himself with supporters of Margaret Thatcher’s government. “Having the Torygraph ranting on about releasing thousands of tons of bombs pushed the whole thing too far into the domain of tastelessness for me,” Minter later wrote. He moved swiftly to pull the game from circulation, but not swiftly enough to forestall criticism from his fellow hobbyists. Popular Computing Weekly published a letter in which a reader lambasted Bomb as “unacceptable” and “sickening.” Nor was this reader alone in his indignation. The Press Complaints Commission, an industry regulator funded by British newspapers and magazines, admonished Llamasoft for the ads it had placed, a move that Minter’s father would later describe, jokingly, as the company’s “first accolade, the 1982 Bad Taste award.”

Minter had no taste for trolling. He wanted to develop games, not controversies. He sent the Commission a letter of apology and returned to Bomb, this time to partially expurgate the game. It was retitled Blitzkrieg, then City Bomber, and references to the war were deleted, reverting the game to “decent anonymity.” In fact, some lipstick traces remained: Argentine flags fly atop Blitzkrieg’s buildings, inexplicably. But the game was entirely Falklands-free by the time it was ported to the ZX Spectrum.

The controversy was soon quelled, due in no small part to the end of fighting on June 14, 1982. By this time Minter had completed Defenda, the Defender clone later known as Andes Attack. He debuted the game at the Third International Commodore Computer Show where it created a small stir. He sold more than 100 copies of Defenda on the convention’s first day and licensed it to a U.S. distributor, Human Engineered Software. Llamasoft was ascendant, and Bomb Buenos Aires was fast becoming the rueful stuff of adolescence.

Two years later, Bomb Buenos Aires merited a brief mention in an editorial condemning Cold War paranoia in computer games. The unsigned editorial describes Bomb as the shameful issue “of a British software house to cash in on the Falklands conflict.” But the game was otherwise forgotten except by devotees of computer games and aficionados of niche moments in their history. It was an interactive joke, one that didn’t land, one that its teller was happy to claw back following the embarrassment that accompanies all such miscarriages.

III. Who’s Laughing Now?

In September 1985, Alexander Macphee, a Guardian reader, wrote a letter to the newspaper’s editors. Few write such letters to pay their compliments, and Macphee belonged to that greater number with an axe to grind. In his letter, pointedly titled “Sanitised Atrocity”, Macphee takes issue with Jack Schofield’s “Anyone for Armageddon?”, an article published the month previous. Schofield, the paper’s computer correspondent, had devoted his column to the defense of computer war games such as Theatre Europe and Raid Over Moscow, objects of heated protest not unlike the kind that scorched Obliterate and Bomb Buenos Aires. Some British shops refused to stock Theatre Europe, and Raid Over Moscow was condemned by no less a person than Monsignor Bruce Kent, then general secretary of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, who thundered against the game, calling it “barbaric and disgusting”. To Schofield, this was just so much hot air. “Computer games are, after all, only games,” he writes. “Not even the simplest child is simple enough to take them for reality.” But this misses the larger point, or so Macphee argues. What concerns him is not the likelihood that children will mistake play war for the real thing, but that such games normalize “organised violence … endow[ing] it with a cultural respectability.” Macphee ends his letter with a sepulchral flourish, paraphrasing Wilfred Owen’s Anthem for Doomed Youth. “We don’t seem to be learning much,” he writes. “The passing-bells are still the monstrous guns”.

Macphee does not argue, as future critics would, that violent video games cause real-world violence, that the two can be definitively linked. Rather, he seems to believe that violent games make real violence more likely by impressing certain ideas into the soft heads of game players (“generally children”), namely the belief that might makes right. Macphee does not elaborate on how these beliefs come to be formed in players’ minds; simple exposure seems to be enough. Thus malformed, and having received insufficient moral instruction to the contrary, children, overexcited by pixelated hostility, come to measure their playground disagreements in scraped knees and bruised knuckles. They grow to voting age and support hawkish politicians. Worse still, they run for public office themselves, groping now not for a joystick but for the proverbial red button.

Perhaps I make too much of Macphee’s argument. Certainly it’s unfair to expect a detailed operation of the influence mechanism he has in mind. His was a letter, not a dissertation. Nevertheless, it’s clear that he believes in a causal relationship between war games and player behavior. Macphee — and the critics Kent, Crookenden, and Cryer — worry that such games coarsen the culture by making players indifferent to the human costs of war. In fact, Macphee references Bomb Buenos Aires with no small scorn, accusing Minter, though not by name, of seeking to deliberately capitalize on tragedy. For what shall it profit a man, Macphee implies, if he sells violent software yet forfeits his soul?

No one has proved a causal link between the playing of violent games and subsequent spasms of real-world violence, and recent studies suggest that no such link exists. But perhaps it’s still wrong somehow to play games about war, regardless of the ways that virtual violence seeps into real-world affairs or doesn’t. Perhaps Macphee is correct insofar as the widespread playing of war games, which are now more sophisticated and engrossing than he could have imagined, damages the solemnity we ought to reserve for matters of life and death. Or perhaps there are cognitive or emotional effects of exposure to media violence that, while posing no physical harm to others, can still be said to harm a player himself by promoting antisocial attitudes or behaviors. I’m skeptical of both claims, but I don’t dismiss them outright. Such effects are important to consider given incipient photorealism, the you-are-there immersion of virtual reality, and the rise of gaming disorders from addiction to indolence.

But I’m less interested in the nature of Obliterate and Bomb Buenos Aires as electronic games than I am in another, longer tradition of which they are part: the tasteless jokes that follow newsworthy disasters. These sick jokes, as they are sometimes known, emerge spontaneously, spreading from a joke-teller to his audience, which members in turn become joke-tellers themselves, provided they find the joke amusing and have occasion to use their new material. Successful jokes inspire elaborations that coalesce into a loose anthology, a joke cycle. Like the news stories from which they are derived, sick jokes are ephemeral, perishable. A cycle will come into existence and travel around the country before dwindling due to overexposure or distance from its source material, or both. Some joke cycles prove especially resilient, spinning for years, even decades. Helen Keller jokes had their heyday in the late 1970s but continue to circulate today.

How to explain the origin of such material, not to mention the eagerness of some to pass sick jokes into the knowledge of others?²⁴ Surely not every author or teller of such jokes is wantonly cruel or sadomasochistic. In Cracking Jokes, a landmark study of the form, Alan Dundes ventures that such jokes are merely modern and especially viral forms of taboo transgression, the desire to speak the unspeakable. “If people knew what they were communicating when they told jokes, the jokes would cease to be effective as socially sanctioned outlets for expressing taboo ideas and subjects,” Dundes writes. “Where there is anxiety, there will be jokes to express that anxiety.”

And what is the anxiety gnawing at the heart of the triumphal Bomb and Obliterate? Not the prospect of Britain’s defeat, surely. A guilty thrill at the excitement of going to war, then, of being not just a witness to historical events but a participant in them? The gathering sense of purpose, unity, and righteousness? Bomb’s inclusion of “Rule, Britannia!” and Obliterate’s reference to Horatio Nelson suggest as much. Why should these stirring sensations be edged by guilt except for war’s grisly accounting? Yet joking about death, even of an implied kind, is common. Such jokes are a universal method of “domesticating something that essentially cannot be tamed,” according to the philosopher Ted Cohen. “Humor in general and jokes in particular are among the most typical and reliable resources we have for meeting these devastating and incomprehensible matters,” he writes. Black humor gives us license to laugh when laughter seems the least appropriate response. Laughter is the life-affirming shout that beats back the black expanse. On this view, it’s acceptable to violate the taboo forbidding jokes about death, but only when the joker’s intentions are therapeutic. And death in Zabel and Minter’s games, though abstracted and only implied, is nevertheless the occasion of fun and levity for their players.

As for the second mistake, it wasn’t treating the war too lightly but treating it too soon. To put Steve Allen’s famous formulation backwards, comedy equals tragedy plus time, and Zabel and Minter had neglected time’s role in that recipe. “Man jokes about the things that depress him,” Allen says, “but he usually waits till a certain amount of time has passed.” Minter and Zabel observed no such propriety. The first draft of Falklands War history was still being written when they pushed their games into the marketplace, and there was little appetite for levity while the threat of death and danger loomed over the live conflict.

Lastly, the pair made light of war, but not to expose its moral horror, nor to rage against its inhuman costs. Theirs was not the satire of Vonnegut and Heller, the kind that exposes corruption, that peels back its disguises, as the satirist Bruce Jay Friedman once put it. Zabel and Minter were, in the end, only joking, in all the ways that ‘only’ implies. Their games could never achieve the noble aims of anti-war iconoclasts, nor did they aim for such lofty heights. Obliterate and Bomb Buenos Aires are games, after all, and flimsy ones at that — blithe and cheerful, wanting only to entertain. As for subtexts, well, just try to find them. Despite the outrage that greeted them, they lack the hard slap of a sick joke’s punch line, the extravagant disregard of propriety. Compare them to a game such as Thatcher’s Techbase, a 2021 first-person shooter that invites players to send the late Margaret Thatcher “back to Hell.” Several of its antagonists include the Baroness’s likeness down to her skirt suits, and the game is dedicated to “everyone that Thatcher hated, and everyone who hated Thatcher.” Speaking to the Guardian—the paper to which Alexander Macphee once wrote to complain about its coverage of war games — an unblushing Jim Purvis, Techbase’s creator, reveals that players can “literally press a button to piss on [cyborg] Thatcher’s grave.” “You can punch her in the face,” he continues, “You can blow her up with a rocket launcher.”

Why delight in the adolescent fantasy of besting one’s political opponents with rockets instead of rhetoric? Why, catharsis, of course. “There’s a lot of people who are peed off with the situation they find themselves in, and the politicians that are leading them, and they’re looking for relatively safe ways to express their frustration,” Purvis explains. If we accept this self-exonerating rationale, then we can divine the conditions that make this kind of satire acceptable in even its crudest manifestations: it conveys a critique, however inarticulate, of a divisive public servant whose political and economic policies were hated by many of her countrymen then and now. What’s more, Purvis waited a judicious amount of time before dancing on Thatcher’s grave; and it didn’t hurt that in the Guardian he had a sympathetic confidante.

The warm reception of Thatcher’s Techbase points to a third way that Zabel and Minter erred, not merely by breaking a taboo but by doing so and not going far enough. Minter’s Bomb had at least one admirer at the Telegraph. Imagine how many more supporters he could have had had he not spared the jingo, or had the game’s satire run in the opposite direction. It seems likely that a game opposing the war would have proved even more controversial given the righteous climate that prevailed at the time of Bomb’s release. In this hypothetical scenario, Minter would have enjoyed support from anti-war activists and possibly from defenders of speech rights and individual expression. Instead, Obliterate and Bomb were nonspecific, milquetoast. Vague enough to offend the perpetually offended, but not specific or incisive enough to win any supporters to their cause. In the end, even their creators weren’t invested enough in the games to keep them on the market in the face of vituperation.

Today, such criticism seems quaint. The culture has coarsened since that summer in 1982; and if that sounds like bosh to you, fine. But consider the multiplicity of channels, kaleidoscopic in their changing, that have come into being since that time, channels that allow every malcontent and mischief-maker to disseminate off-color content far and wide. Offensive sentiments, many times more offensive than the ones encoded in Obliterate and Bomb, circulate every second on social media, not to mention SuperFund sites such as 4chan and its ilk. Given the weakness of Minter and Zabel’s provocations, it’s doubtful that either one would be subject to cancellation were their stories reenacted today. More likely they would suffer the same storm of criticism: more immediate and intensely felt, perhaps, but just as short-lived. Nothing that locking one’s Twitter account and touching grass couldn’t rectify.

But then the media ecosystem itself, the one that propounded the stories of Obliterate and Bomb, has changed beyond all recognition, splintered into a thousand thousand branches, sects, and subdivisions. One consequence of this fragmentation has been a vitiation of the social norms that checked rude behavior of the kind discussed in this essay: the knowledge of having trespassed against fellow citizens, and the desire, however reluctantly embraced, to make amends in order to remain a community member in good standing. Where else could one go, after all, in those days of real places, inhabited by the body as well as the mind? Today, on the internet, there’s always somewhere else to go; and unless the offense is grave enough, the people there — ciphers, really — won’t care all that much what you said or did. Even a megalopolis like London in the 1980s seems downright provincial next to the worlds-within-worlds of the internet. The sense that we are linked to unknown others, however tenuously, that we depend on them and they on us, that we should feel badly when we inadvertently hurt them, as both Minter and Zabel felt; well, these virtues are hardly extinct, but neither are they as sturdy as they were four decades ago. And so you might look on Obliterate and Bomb as I do, with nostalgia, not only for their touching crudity, their handmade quality, but for the vanished world glimpsed at their margins.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the role of response frames in Obliterate’s game mechanics.

Works Cited

[1] Lawrence Freedman. Britain and the Falklands War, Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 1988, pp. 94–95.

[2] Enoch Powell. “This New Unity that Our Leaders Must Not Betray,” The Times, 14 May 1982, p. 10.

[3] “I suppose it must be said that this tape is the most disgusting artefact ever recorded (it makes Judge Dredd sound like Cliff Richard), and if you decide — more fool you — to take it seriously it will be the most offensive thing you’ve ever heard; I can guarantee that. But as I’ve said before, anyone who takes the Macc Lads seriously is a total wally.” See: John Opposition. “A Country Fit for Herberts,” Sounds, 5 March 1983, p. 26.

[4] The first vessel to arrive was the HMS Spartan, a nuclear-powered submarine that sailed for the Falklands on March 30, arriving on April 12. See: Max Hastings and Simon Jenkins. The Battle for the Falklands (New York: Norton, 1984), 61.

[5] W. R. Broadhead. “Prestel: The First Year of Public Service.” The Post Office Electrical Engineers’ Journal, vol. 74, no. 2, 1981, p. 129.

[6] Gary Zabel. “Experiences of a Regional Newspaper Publisher on Prestel.” Videotex: Key to the Information Revolution. Proceedings of Videotex ’82: The International Conference and Exhibition on Videotex, Viewdata, and Teletext. New York, 28–30 June 1982. Northwood Hills, Middlesex, UK: Online Publications, Ltd. 1982, pp. 60–61.

[7] Ibid, p. 62.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ian Watson. “New TV system switched on for a lucky few.” Sunday Telegraph, 1 Apr. 1979, p. 21.

[10] Gary Zabel, in conversation with the author, January 7, 2020.

[11] Rob O’Donnell, proprietor of viewdata.org.uk, explains the mechanics of Obliterate, and games like it, thusly:

Prestel page numbers were, indeed, 1–9 digits long. Information providers rented a 3-digit node and could create pages by extending this number. Each page could have up to 26 frames, a-z, and users would access them by pressing # to progress to the next one. So, Mercury 332 owned 332a; they could then create pages 3329a and 33291a (every page had to have an existing parent.) Users could either call up a page directly, or press a single digit, 0–9, to go to a pre-defined follow-on page. Each of these links was defined in the editor; and whilst a default pointed each digit to the matching child page, they could actually route anywhere. Most games, therefore, were essentially multiple choice at each “turn.” Press the wrong number, you lost, and were routed directly to a “game over” page. Press the right number, you progressed to the next question. Of course, the designer could be clever and offer multiple routes to progress, and vary the results; but there was no way to track a score or do anything complicated. All you could do was create a pile of static, fixed pages with clever linking between them.

[12] Bill Wadsworth, email message to author, September 7, 2021.

[13] Gary Zabel, in conversation with the author, January 7, 2020.

[14] Gary Zabel, email message to author, July 28, 2021.

[15] Patrick O’Leary, “Push-button shopping arrives.” The Times, 14 Jan. 1982, p. XII.

[16] Robin Young, “The first 18 months of Prestel.” The Times, 27 Apr. 1981, p. 19.

[17] Roland Gribben. “Why Buzby is only getting slightly ruffled.” Daily Telegraph, 30 September 1981, p. 18.

[18] Zabel, Gary. “Experiences of a Regional Newspaper Publisher on Prestel.” Videotex: Key to the Information Revolution. Proceedings of Videotex ’82: The International Conference and Exhibition on Videotex, Viewdata, and Teletext. New York, 28–30 June 1982. Northwood Hills, Middlesex, UK: Online Publications, Ltd. 1982, p. 62.

[19] The reference to Fray Bentos was made in ignorance of a skirmish that occurred during the First World War, at the Battle of Passchendaele, in which nine crew members of a British Mark IV tank were besieged by German infantry after their tank got stuck in a crater. The tank’s captain, Donald Richardson, had been a wholesale grocer who sold Fray Bentos tinned meats. The grim comparison must have come to him all too easily.

[20] “Now–The TV War Game.” Daily Mirror, 10 April 1982, p.1.

[21] Gary Zabel, in conversation with the author, January 7, 2020.

[22] Gary Zabel, “Prestel is a household name … due to our game!” Mercury 332 Viewdata Newsletter, issue one, summer 1982, p. 1

[23] Zabel, Gary. “Experiences of a Regional Newspaper Publisher on Prestel.” Videotex: Key to the Information Revolution. Proceedings of Videotex ’82: The International Conference and Exhibition on Videotex, Viewdata, and Teletext. New York, 28–30 June 1982. Northwood Hills, Middlesex, UK: Online Publications, Ltd. 1982, p. 66.

[24] In the case of the Falklands War, the fighting was brief, its resolution swift and certain. The war was too abrupt to birth a joke cycle, nor did events ripple outward in such a way as to inspire jokey derivations. Which isn’t to say that no Falklands jokes were authored. Here’s a fine one from Reddit user Djidell.